"Regenerate Outcomes are delighted to be working with the pioneering team at Sapperton Wilder. Within our soil health programme, Sapperton is learning how to make the transition from conventional to regenerative farming from an experienced team of advisors led by Gabe Brown and Dr. Allen Williams. The climate impact of this transition is being monitored to the Verified Carbon Standard which involves repeated laboratory measurements of soil organic carbon stocks and third-party verification of outcomes."

- Tom Dillon, Director, Regenerate Outcomes

To achieve our goals of improving biodiversity on the farm alongside better socio-economic returns, we are adopting some of the principles and practices of regenerative farming. In areas of 'marginal' land or on farms like ours with degraded soils, there is a great opportunity to test more sustainable farming systems. Typically, these areas have been low yielding, less productive, and therefore less profitable and heavily reliant on subsidies to keep them afloat depending on scale.

Some areas that are very fertile are much more suited to prioritising food production and are less likely to adapt their economic model and high yielding food output into a framework that is able to focus on biodiversity outcomes in the same way. With subsidy systems shifting towards payments for specific environmental benefits, projects and farms like Sapperton Wilder are an opportunity to champion better biodiversity outcomes, improve soils, and attempt food production in more sustainable ways. Sapperton Wilder aims to showcase some of the ways to achieve this.

Reimagining healthier and more sustainable farming systems that work with natural processes, tackle carbon emissions more rigorously, and provide the opportunity to improve biodiversity is a huge challenge. Regenerative farming is an approach to food and fibre production that work sympathetically with the environment.

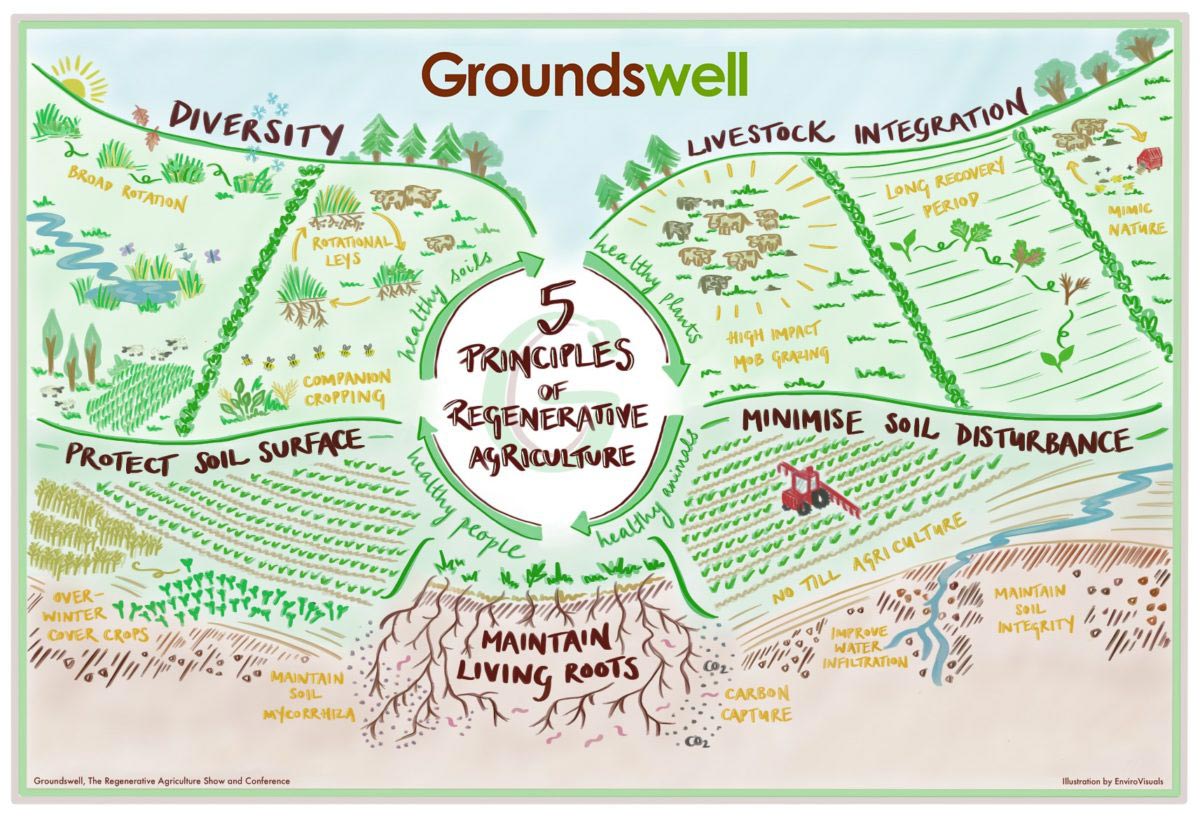

There are five main principles being adopted at Sapperton Wilder

- Minimize soil disturbance

Soil supports a complex network of worm-holes, fungal hyphae and a labyrinth of microscopic air pockets surrounded by aggregates of soil particles. Disturbing this, by ploughing or heavy doses of fertiliser or sprays, will set the system back. - Keep the soil surface covered

The impact of rain drops or burning rays of sun or frost can all harm the soil. A duvet of growing crops, or stubble residues, will protect it. - Keep living roots in the soil

In an arable rotation there will be times when this is hard to do but living roots in the soil are vital for feeding the creatures at the base of the soil food web; the bacteria and fungi that provide food for the protozoa, arthropods and higher creatures further up the chain. They also keep mycorrhizal fungi alive and thriving and these symbionts are vital for nourishing most plants and will thus provide a free fertilising and watering service for crops. - Grow a diverse range of crops

Ideally at the same time, like in a meadow. Monocultures do not happen in nature and our soil creatures thrive on variety. Companion cropping (two crops are grown at once and separated after harvest) can be successful. Cover cropping, (growing a crop which is not taken to harvest but helps protect and feed the soil) will also have the happy effect of capturing sunlight and feeding that energy to the subterranean world, at a time when traditionally the land would have been bare. - Bring grazing animals back to the land

This is more than a nod to the permanent pasture analogy, it allows arable farmers to rest their land for one, two or more years and then graze multispecies leys. These leys are great in themselves for feeding the soil and when you add the benefit of mob-grazed livestock, it supercharges the impact on the soil.

“If you are starting with a permanent pasture, as is nearly 70% of agricultural land in the UK, you might think that you’re already regenerating. However, in the name of improvement, a lot of this land has been ploughed up and reseeded or heavily fertilised and poorly grazed. Instigating a holistically managed grazing regime will transform the soil and the pasture that it grows. A surprising amount of grazing land is actually monocultural, regularly disturbed and is poorly covered. In the wetter and hillier parts of the country this is often enough to cause increased erosion and flooding.

No-one is really sure how good we can make our soils, nay-sayers will tell you, for instance, that there is a limit to how much Carbon soils can sequester. That could be true if soils were only operating in the top six inches, whereas we’ve seen topsoils getting deeper and deeper as time goes on, meaning a greater sponge to hold rainwater and for the roots and fungal mycelium to operate in, and making ever more room for safe long-term Carbon storage. Regenerative farming isn’t just good for farmers, it is really the only way, if performed across the globe, that humanity can have any hope of living on a pleasant planet.”

- John Cherry- Weston Park Farms and co-founder of Groundswell.

With kind permission from Groundswell, John Cherry and Rebecca Roberts. Infographic credit ‘Groundswell’ and illustrator is Rebecca Roberts (Envirovisuals). 5 Principles credit ‘Groundswell’ and farmer John Cherry.